In the last half-century the church, namely small Christian-American denominations, have become noticeably more liberal in embracing the commercial techniques of selling, and this is evident in the largely urban phenomenon of the storefront church. An increasingly-apparent secularization of the traditional church by "mass marketing" may stem from a number of reasons, likely the most important of which is the necessity for boosting attendance and ultimately membership. While church attendance since the 1990's has remained relatively stable in America, a general trend since the 1940's indicates that attendance has fallen back to WWII levels after a decade-long peak in the 1950's. From this it can be inferred that in times of prosperity, general church attendance reflects economic optimism. Attendance followed post-war prosperity - suburbanization and commercial culture in the form of the shopping mall, which is significant in understanding the church's current urban situation and future implications from both an architectural and institutional standpoint. The unapologetic incorporation of elements of secular culture point to a relationship with the function and aim of the mall - a model serving a range of church sub-types. Over decades churches have adapted the traditional model of service or mass-only to that of extra-religious, community-oriented services - youth music groups or ministries, bible camps, sports groups, soup kitchens, etc. demanding an equal adaptation of the function of church facilities themselves. Such multi-program churches, Union Church of Hinsdale for example, can be understood as modern precedents to the church's contemporary state of secular absorption. While this sub-type could be traced back to the closed-model abbey or monastery where its functions served the needs of exclusive monastic groups, the multi-program church offers a modern buffet of other forms of religious, community-oriented participation beyond mass or service. Consequently, mass, and therefore worship, has become simply another type of church service as opposed to the primary function.

Considering the adaptation to the crass-commercial model and the subsequent shift in the importance of worship, what accounts for today's proliferation of the storefront church, aside from the diversity of denominations, is unique in the history of church types. Not only is the storefront church an explicit and holistic expression of the merger between church and commerce in terms of architecture and operation, but its existence and more particularly the way it exists is indicative of a corresponding demand by many middle to lower income, often ethnic, communities. This reductive sub-type is not necessarily new1 either, but its modern implementation has certainly reached new heights of secular transformation where many of the traditional elements in architecture and function have been replaced by secular, borderline-sacrilegious counterparts. Further, the storefront church, by default of its current architecture, interior, and business situation, has ironically and unwittingly restored the importance of the mass which is one of the few, if not the only, services it can provide. It is tied in property to its neighbors, space is often limited to a singular room which can only be reserved for its most important functions (the mass), and financially it is often limited in its operation to a primary function (also the mass). Counterintuitive to these constraints, the church's dissemination into smaller identities or inconspicuous storefronts, has allowed it to remain tightly bound to the practice of worship. Monumentality has given way to modesty, which has proven equally successful, while space has been sacrificed but apparently not faith. Historically, large-congregation churches have always been weighty investments as religious centralizations of a larger community but, in their authority and monumentality, have also been "intimidating" and thereby alienating entities unable to connect more intimately to the individual. Where larger church institutions may be seen as intimidating and un-representative of some communities - bourgeois perhaps - storefront churches have stepped in to become "working-class" models of community worship that are more reflective and receptive to the tastes and "simpler" needs of middle or lower-income groups in the same way that fast-food, the corner liquor store, or 7-11 is convenient and undemanding. The modern insistence on instant gratification has forced the church into a precarious position - that of balancing its traditional mores in an "attention-deficit" society while deploying the same attention-seeking techniques as the modern business. The "speed" of worship has thereby demanded shifts in focus subsequently resulting in shifts in image. Specifically, the storefront church demonstrates the church's appropriation of the commercial mainstream by the reduction of ornament and symbol to sign and the replacement of "the sacred" with "the secular". The untouchable and timeless have become commodified and transient, and this transference has manifested most crudely and reductively in storefront churches, but also notably include converted types which are secular storefronts themselves.

The Chicago Tabernacle is one such example that has adopted the refurbished shell of a secular institution - a retrofit church into a theater, which is a likely reason for its re-adaption considering that the theater is arguably closest in type to the church. The only way to identify the Tabernacle as a church, however, is through its street-side marquee - specifically the word "Tabernacle" and its association to Christianity, while its facade elements remain essentially attached to the theater type. A typical stained glass motif of a traditional church is replaced by standard glazing. An ornamental parapet replaces an iconic steeple. It also fails to escape the theater type in the moment when a cross would in fact help even if only as a passing clue. Meanwhile, its innards are set up to serve both the needs of a theater production and that of a worship production, adopting the stage for performances of a more spiritual thread. Similarly, the Philadelphia Church's prior existence as a 1940's era bank is minimally convincing of its spiritual affiliations aside from its name on an awning and a now-iconic "Jesus Saves" sign, which become the facade's most prominent and recognizable characteristics. Generally, converted types become dependent on the identification of pre-existing features that served pre-existing needs and groups, and therefore poorly manage their assimilation by association and advertising appliques.

The storefront church on the other hand is defined by reduction, informality and a subsequent loss of any monumentality which all in fact serve its best interests. Where the converted type is masking any notion of "cheapness" or "copping out" to secularization, the storefront church is admitting to and embracing it - an acknowledgement of the desire for speed and convenience as well as a recognition of the "simplicity" of the mass and its targeted demographic.

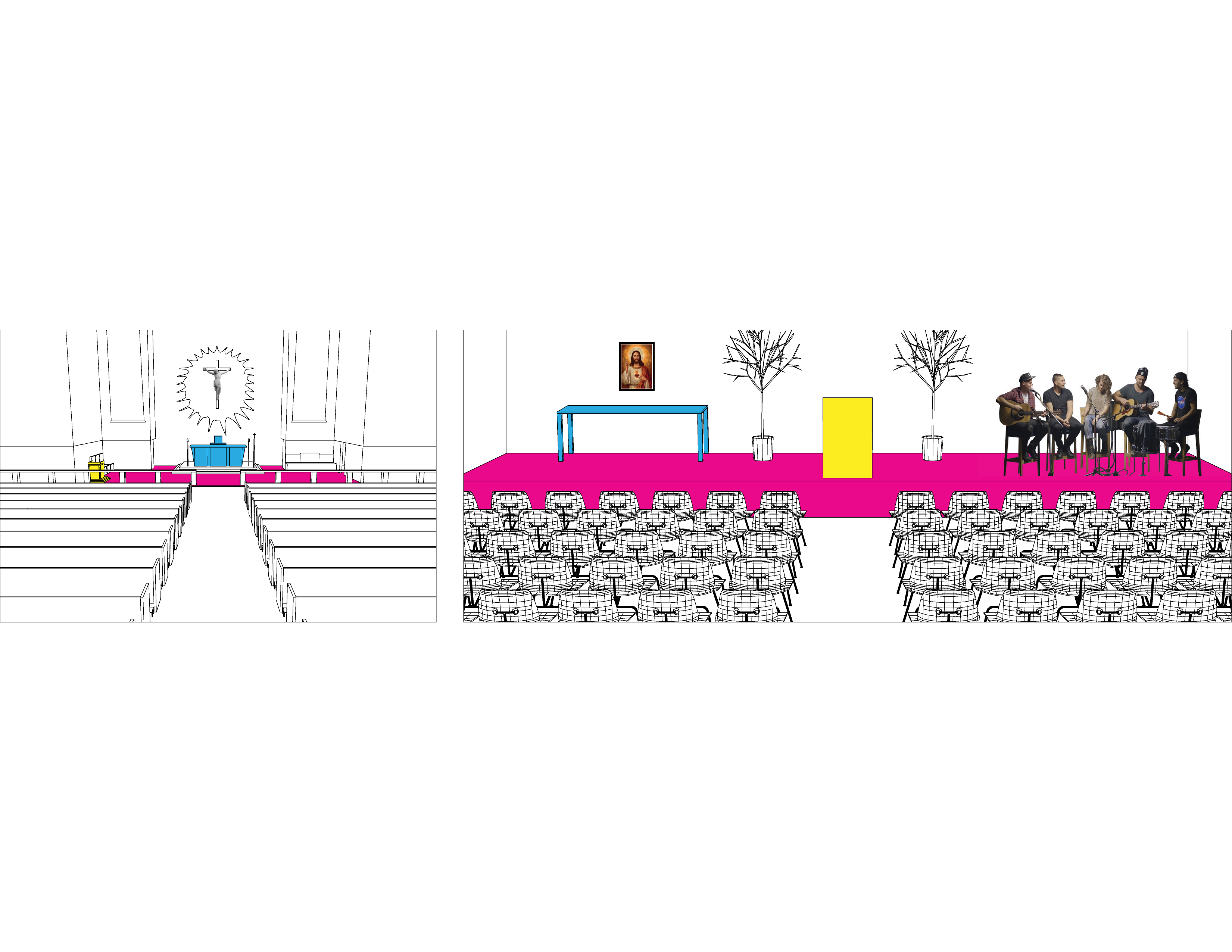

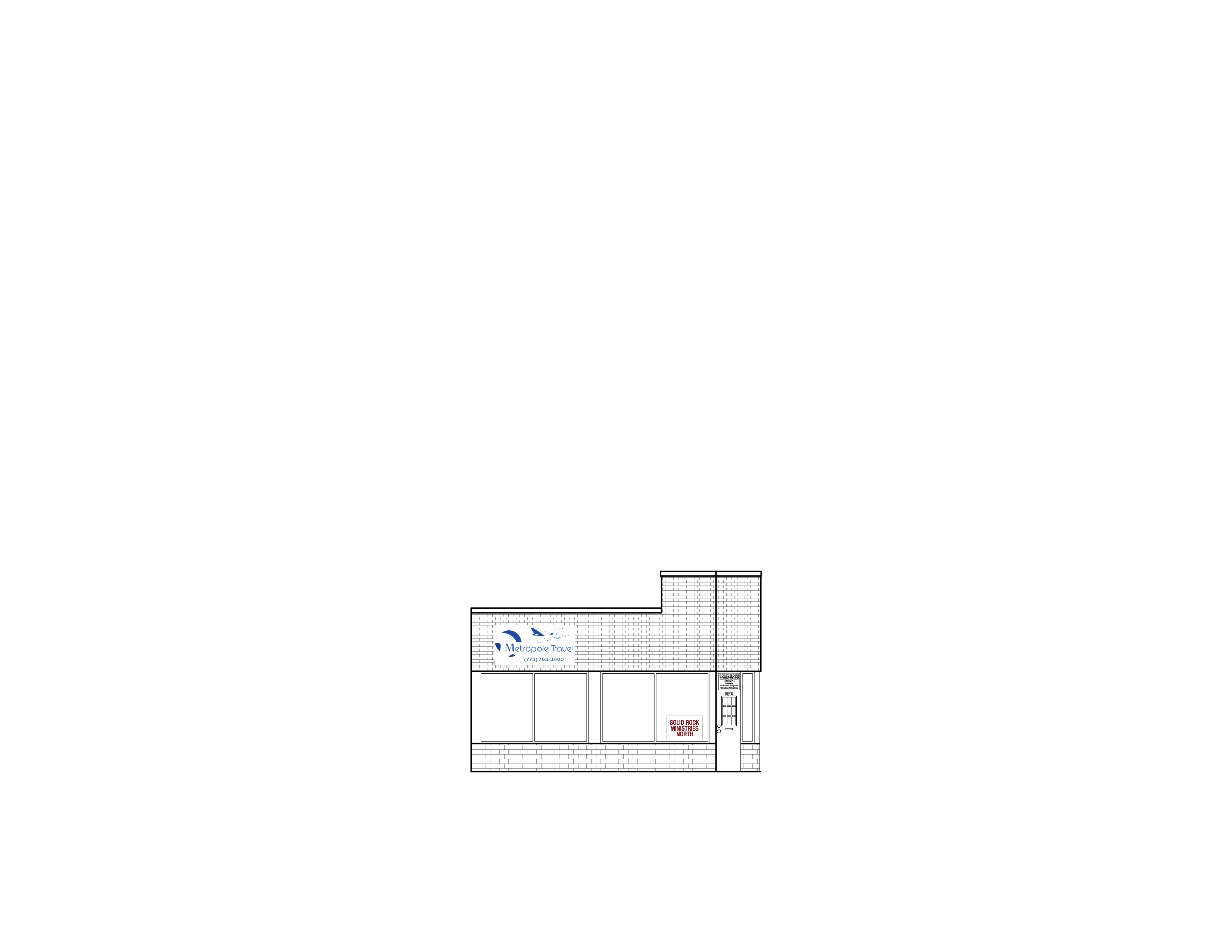

Solid Rock Ministries North demonstrates a nearly complete absorption and acceptance of the commercial reality. A homogeneous brick facade camouflages its position adjacent to a travel agency - the only things giving it away being a parapet, a simply printed placard against a window, and a nearly-illegible yet descriptive sign posted on its entrance. Seen nearly whole from the exterior, one could assume, and would likely be correct, that its interior is equally lacking. The loss of attention to detail concurrent with the demand for convenience and expedience is not only evident on the banal, faceless exteriors of nearly all storefront churches, but also on their interiors where traditional elements, from furniture to sacred objects and banners, have been reduced to secular replacements. An altar is often entirely transformed into some type of stage, or a simple podium might entirely replace the stage, altar and sanctuary. Normally a small band or a single person on a keyboard would suffice as replacements for a grandiose organ or choir. In plan, many storefront churches adapt the Latin cross approach of the traditional church in the arrangement of chairs and the location of a stage, but form is essentially reduced beyond recognition to that of the commercial box.

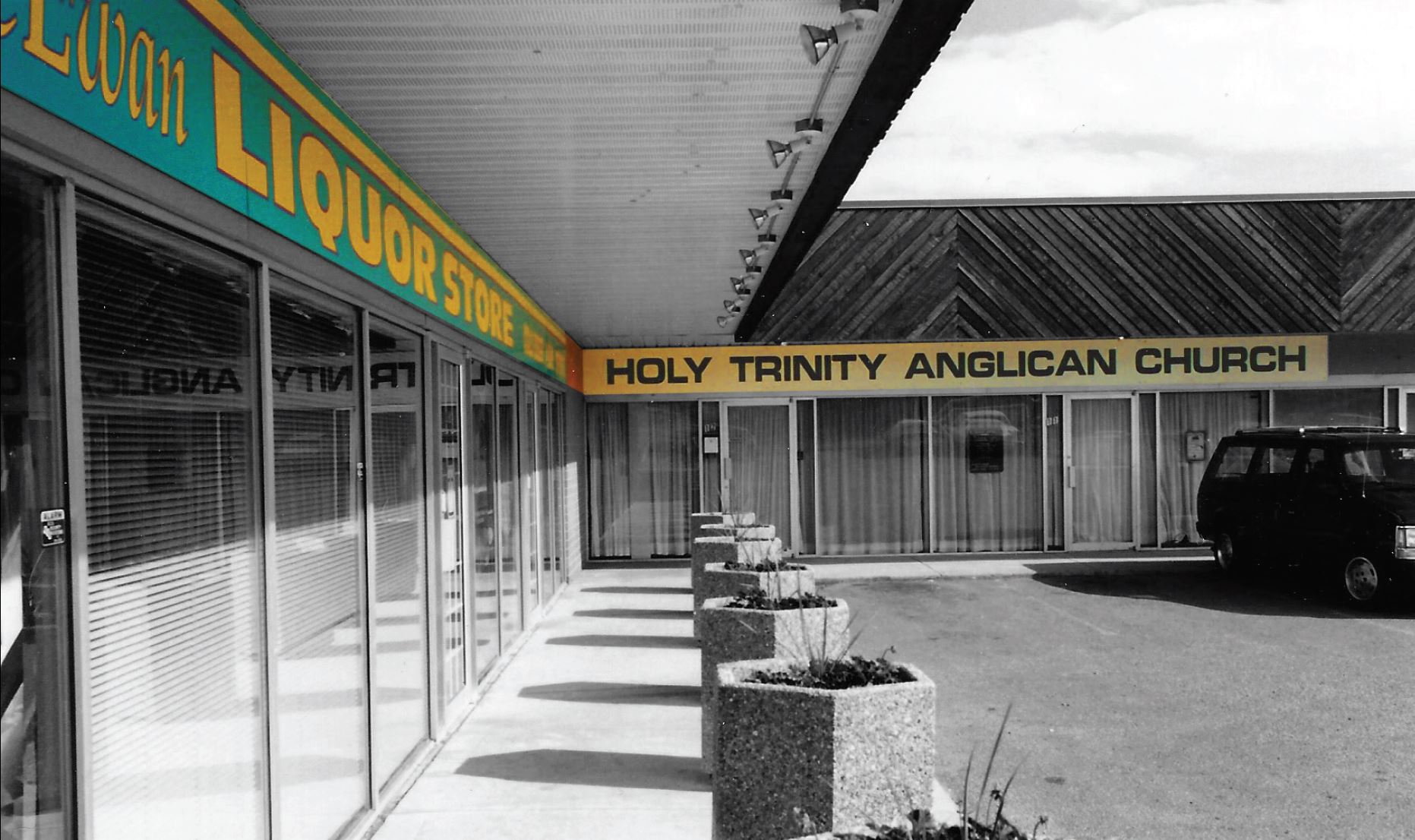

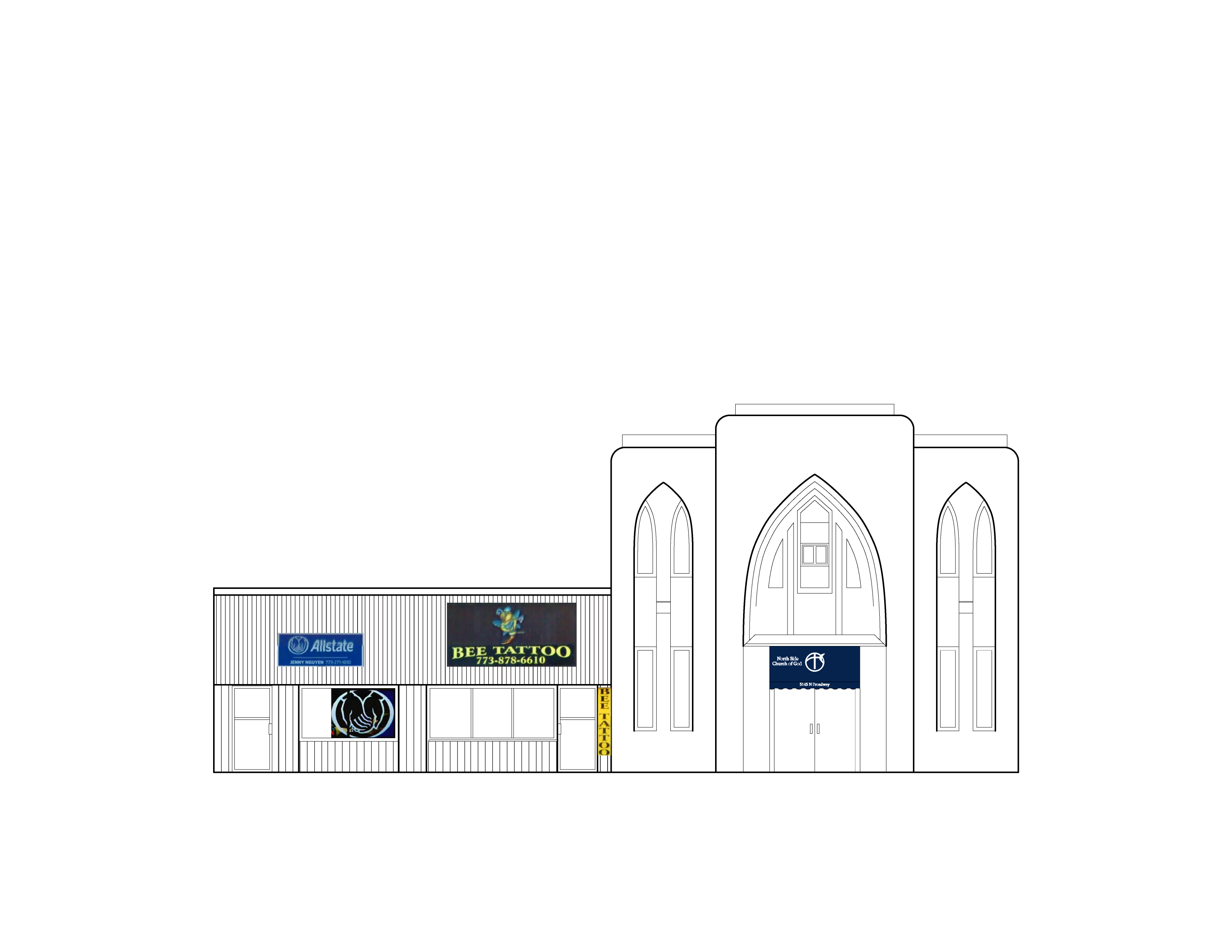

Storefront churches are often located with immediate adjacency to retail and other services to the point where commercial proximity and adoption in their variety or depth bear little significance to the church architecturally but could in some ways be detrimental to the church's moral obligations. The North Side Church of God and Holy Trinity Anglican Church seemingly accept the existence of their neighbors, a tattoo parlor and liquor store respectively, without concern for the ironic juxtaposition of what would normally be considered sinful - bodily desecration and alcoholism. Whether either of them appeared first or not is of less importance than the complete moral indifference in the relationship between church and commerce as demonstrated in their seemingly haphazard zoning. The storefront church's dependence on commercial context for wayfinding purposes, however, can easily be located in its primary means of public communication - the sign being the only identifier of church and indicative of its conformity - inconspicuous in its ironic blending and association with similarly indifferent retail stores. There is no easily identifiable figure in elevation nor plan - absorption has reached an extent that familiarity comes from solely the signage itself applied to an essentially unassuming facade. Further, it is often its own commercial surroundings that makes itself more apparent; i.e. the storefront church depends on the signage of adjacent businesses as much as its own, working to its advantage in terms of publicity and recognition.

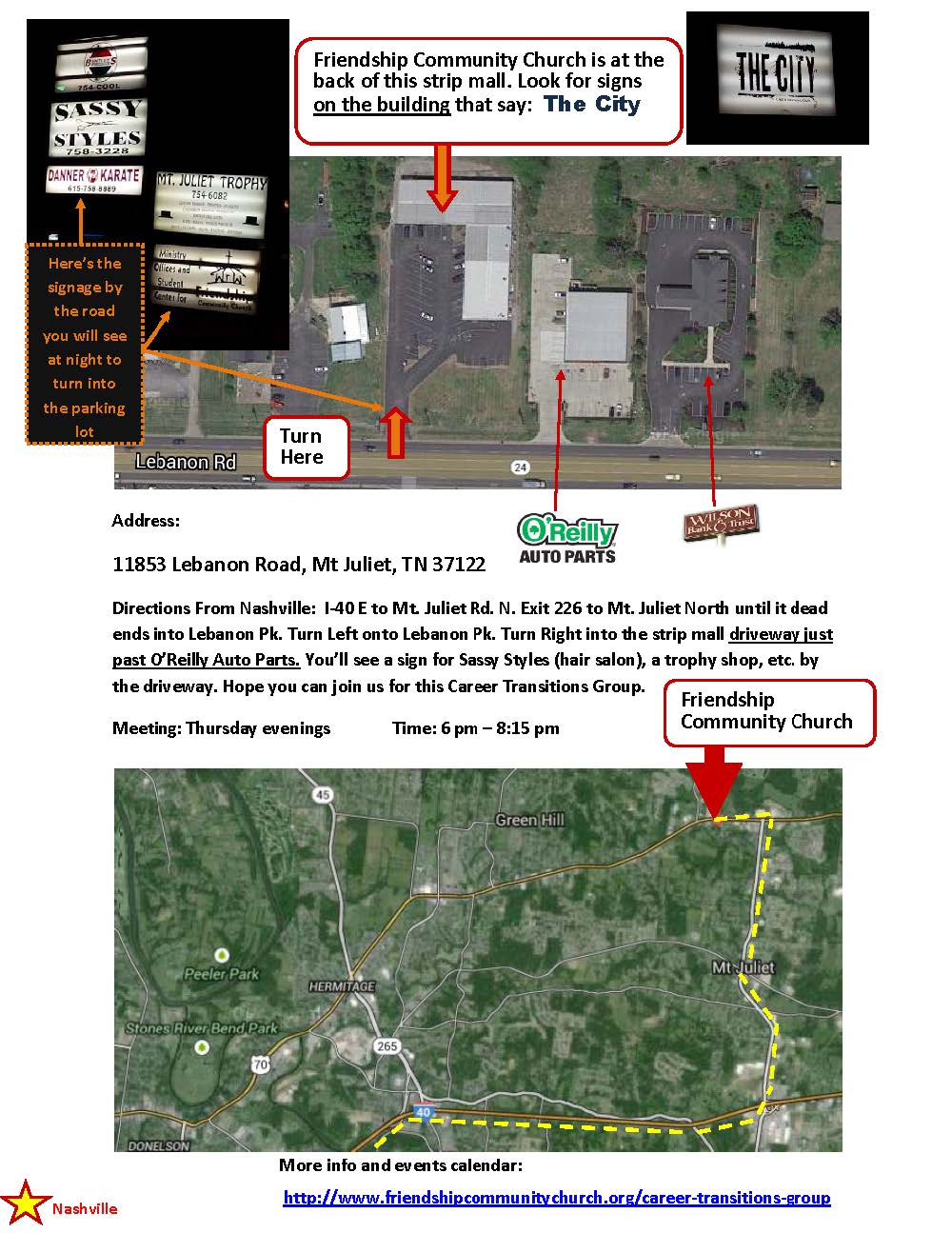

The directional flyer for the Friendship Community Church exemplifies the significance of the sign and especially the importance of contextual signage in relationship to the storefront church. The flyer's designer made sure that one should, while driving down Interstate 24, be sure to recognize the O'Reilly Auto Parts and Wilson Bank & Trust first, in order to locate the entrance to the strip mall behind which is the church. Contextual signage in this case becomes geographically significant in locating the church. Secular adaptations, relatively cheap property, and the ease of advertising in conjunction with a need for accessibility and convenience further imply a drive-thru aesthetic - a new "speed" of worship and faith where religious symbol has been swapped for the marquee, road sign or banner - devoid of any meaning but typically hollow references. Additionally, speed not only means the incorporation of forms of attention-grabbing entertainment or signage but a potential shift of the direction of the church itself from that of an exclusive, bourgeois "cult" to perhaps an entity with greater communal tolerance even if it implies its architectural demotion. Many others may be more reduced and anonymous, but the goal remains the same - to expediently convey an open and accessible faith shed of intimidating monumentality, ceremony or authority for patches of often low-income urban communities.

If it wasn't clear before that skyscrapers are the new cathedrals, commercialism our faith, and money our god, then the state of the church today, in embracing the commercial mechanisms born of capitalism that it has paradoxically attempted to alleviate throughout history, has only made these analogies more potent. Despite the widespread reduction, replacement and absorption demonstrated by storefront churches, there is no real indication of a "decline" in the church as an institution. About fifty-six percent of Americans say there is still a place for faith in their lives, and given the behavior of adopting from the secular mainstream; i.e. pop, mass culture, advertising, etc. it seems the church has become less, if not equally, concerned about upholding dogma than acquiring membership. The importance of worship, however, is ever more questionable as the individuals that make up a fast-paced society are at odds with a traditionally and historically-rooted, "slow", institution. Attendance trends over the last half-century reflect this notion. The church can still serve as a conservative moral foundation which is still largely detached from the affairs of the market and world events at least in public, yet it is subtly becoming undermined by commercial and cultural elements that have made inroads over time in the church's traditional arenas. History has shown, however, that the church is malleable in practice and teaching - proof being found in its resilience throughout centuries. The notion of the church reaching into the secular realm for societal relevance, therefore, is nothing new, but the common fusion of the church and commerce in type and technique today is rather unique in history. Today we can find many of the values and mores taught in service or mass in many secular areas. Modern life has allowed us to discern or distill the lessons of religion without prejudice to art and philosophy; i.e. today those lessons can arguably exist without reference to religion. The arts for example teach us often indirectly or through their own philosophies the same lessons we can learn from scripture and worship, and can often be just as adept at facilitating community if not more so. As a consequence of greater secular adaptation in the institution's ambitions, church design has remained largely indifferent contextually (often creating its own such as with multi-program churches) and architecturally (as with conversions and storefront churches) compared to more sophisticated approaches in earlier ages2 where churches were as much status as spiritual symbols of entire communities.

Additionally, location has played a stronger role in the general perception of the church today - as an institution that transcends its type (as the idea of home transcends the house) though still requires the type to enforce that transcendence. On Sunday, we must always go to church rather than church coming to us and this often recalls the drudgery of traveling to a contemplative building with a steeple, pews, altar, and participating in listless droning. Storefront or converted church types attempt to alleviate the tendency for people to produce the banal images commonly associated with Sunday mass through the substitution of traditional with quasi-religious transplants as well as by association with neighboring businesses. At the very least the storefront church becomes simply another typological transformation in a long history of them, but a transformation that is likely a dead end in the current socioeconomic state, beyond which one can only imagine a completely dissolved type-less church - an architectural problem that should be confronted today in anticipation of post-capitalist solutions.

Considering the essential components of worship - a celebrant, congregation, and some artistic form that encourages participation - the type-less church may not be any particular building per se but rather simply a shoddy assembly of stage or set pieces - readymade plug-and-pray. More importantly, would the post-capitalist church be so embedded in secular culture that its definitions and therefore its players change beyond recognition, and what was once seen as purely secular become largely informed by what was religious? Priest or celebrant may become something less symbolic and sacred and more practical - perhaps "community leaders" who are active participants or consultants in a variety of secular areas - while parishioners relinquish their identification with denominations and simply remain active "community members" with a variety of theological tolerances and affinities. Alternatively, could the "miracles" of science and technology become categorized or perceived as types of holy interventions by our leaders in lab coats? Church could no longer exist as a building nor an institution, but more purely as an ideology of living in accordance with a set of moral principles largely distanced from theology or altogether shedding its theological ties - the storefront church serving as an early precedent or proto-type-less church. Maybe it will no longer be so much about the medium, but rather the massage.

1. The storefront church can be traced back to Jim Crow-era Bible Belt Baptist churches that served as scrappy safe-havens for alienated African-American communities. In this case, storefront churches were as much centers of worship as centers for civic resources.

2. Since the Middle Ages until at least the Enlightenment when arguably the church and religion in general were challenged by reason, positioning humans as bearers of their own destiny.